Fireball Island: Art in Board Games #49

Just as in any artwork, an artist's most valuable tools are composition, scale, contrast, tone, color and pose. When dealing with large, detailed scenes with complete background and many characters it's very easy to become overloaded..

EDITORS NOTE: This interview is with talented artist George Doutsiopoulos, who joined me on the site last year (you can see that interview here). I’ve long wanted to take a closer look into how box art is created and George was kind enough to let me interview him about his work on Fireball Island and it’s expansions. I hope to do more of these cover story interviews next year so if you have any suggestions for games, let me know in the comments or on social media.

Hi George, great to have you back on the site! Since we last spoke you've been working on the wonderful remake of Fireball Island. Can you tell us how you got involved in that project and what was your role?

Hi Ross, I'm really happy to be back, thanks for having me for a second time! Back in October 2017 I was approached by Jason Taylor, the art director from Restoration Games, who was looking for artists for the new Fireball Island board game. There was lots of art that needed to be done: boxtop art, card art, etc and the styles of the participating artists had to look good together and not clash with each other, so that part took time. Jason was very considerate and let us propose what kind of art we would rather take on. I felt I was a better fit for the boxtop art and Jason assigned it to me.

Fireball Island box cover - Initial sketch concept art

When creating the cover art for the Fireball Island base game box, what kind of mood or style were you looking to create and how did you try to achieve it?

Thankfully, the brief I received was great, as was the communication with the art director: detailed, thorough, concrete and fun. There were very specific comments regarding the color palette and the elements of the illustration (for example the burning tree, collapsing bridge, cut off rushing rapids were there from the beginning). Regarding style, Restoration games wanted to go for something that was epic but with healthy doses of slapstick and fun. Something with toon sensibilities but not childish, and detailed enough to attract all ages. That was really amazing because this artistic style that is part realism and part cartoon comes very natural to me.

Fireball Island box cover - Second sketch concept art

We also wanted an illustration where the island itself is prominent (mainly, Vul-Kar the volcano) and wanted distinct levels (foreground, midground, background). At first, as you can see in the sketches, I focused too much on the epic and slapstick aspects and created a concept that was fun but very busy. With the valuable guidance of Jason, we finally came up with a composition that had fewer characters but was more powerful.

Fireball Island box cover - Final sketch concept art

You also worked on the box art for the expansions, 'Wreck of Crimson Cutlass', 'The Last Adventurer' and 'Crouching Tiger, Hidden Bees'. The artwork on the box for the last two made up a greater image when combined so how did you manage to make both boxes interesting, yet work together in this way?

That idea was entirely Jason's (Editor: Jason contacted me to state the idea originally came from designer Rob Daviau) and I loved it as soon as he mentioned it. I hadn't done something like this before but I welcomed the challenge. Of course, creating a composition that needed to work as a simple illustration AND as two standalone illustrations sounded difficult at first, but it turns out it was easier than I feared. I worked with a lot of quick drafts, first focusing on the separate boxes without minding myself with the larger composition yet, to make sure the separate compositions were interesting by themselves.

Fireball Island - The Last Adventurer Expansion box art

Fireball Island - Crouching Tiger, Hidden Bees Expansion box art

When sketching I kept the Fireball Island logo in place because it's a very prominent visual element of the box and I wanted to take it into account from the beginning. When I came up with drafts I was satisfied with I combined the ones that worked into the larger composition, made any revisions necessary and was ready to start sketching and painting. I painted the final artwork as a single illustration, mainly to make sure the separate boxes join perfectly when standing next to each other.

Fireball Island - The Last Adventurer and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Bees Expansions complete box art

The box covers are packed full of energy, so what are some ways an artist can inject that into their creations?

Just as in any artwork, an artist's most valuable tools are composition, scale, contrast, tone, color and pose. When dealing with large, detailed scenes with complete background and many characters it's very easy to become overloaded, so I keep my approach as simple as possible: start from the big and overall and end with the small and detailed. That means that during the sketching phase I was at first concerned with the overall volumes and shapes (very important for the impression of movement and speed), with focal points and compositional axes (to create an appealing composition that helps guide the viewer's eye), with scale (to create the illusion of depth and perspective) and with pose (to create dramatic poses and expressions that further help create the illusion of action and movement). Then I experimented with color drafts, before moving on to painting the actual illustration. For me, making all the colors work in very large compositions is probably the hardest part so I spend as much time as I need to figure my palettes out.

Fireball Island - Crimson Cutlass Expansion box art

Choosing the local colors is not enough, not by far. I need a chromatic theme for consistency and character (Fireball has a lot of warm colours, for obvious reasons) and I needed to separate areas of primary, secondary and tertiary interest using warm and cool colors, contrasting and complementary hues and tonal contrast. I'm still getting the hang of this and feel I have a lot of room for improvement!

Fireball Island - Final product shot

Before you leave us again, what are you working on next?

Right now I'm working on a few different projects, the most fun and interesting one being the work I am doing for Arkhane Asylum Publishing in France. They are a classic role-playing game publishing company and I am currently illustrating the characters for their upcoming game "Malefices", set in Paris of the 1900s. They reached out after seeing some vintage ink illustrations in my portfolio which they felt were right for their book. It's a style quite different from Fireball Island but one I also really love working in!

EDITOR: You can find George’s portfolio here and see more about Fireball Island on Restoration Games website here.

(All illustrations copyright of George Doutsiopoulos, product shot by Restoration Games)

Up to 4 Players: Art in Board Games #48

From the illustration side, it takes about 10 hours to produce a page (back when we did short strips it was more like 3-4 hours). I wish I could reduce it somehow, but I wouldn't want to sacrifice either the style and level of detail we established, or the "amount" of plot we manage to get into every page; since we post a new page only once a week, we want each update to be worth the wait.

EDITORS NOTE: While this isn’t quite board games I couldn’t be happier to be speaking with the two creative minds behind, Up to 4 Players, a weekly web comic that tells the story of a group of friends playing an RPG together. They’ve also created a roleplaying game based on the Crystal Heart comic strip, currently on Kickstarter. Now on to the interview!

Hello Aviv and Eran, thanks for taking the time to speak to us. Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about yourselves?

Aviv: Hi Ross! Thank you for having us on, even though we don't technically do art in board games. I am a freelance illustrator, specialising in character art and comics. My passion for drawing started with the animated X-Men series from the 90s (of course I created my own super-hero group that was almost, but not quite, EXACTLY like the X-Men), so action, fantasy, and colourful, bigger-than-life characters have always been my cup of super-powered tea. Later, thanks to Eran, I got into the amazing hobby of roleplaying games, and that has become a major inspiration too. I've lived in Israel most of my life, and thanks to the internet I was able to expand my knowledge, skills, and social network, especially around those hobbies that were (and still are, although to a lesser extent) somewhat fringe in our small country. I moved to London 5 years ago because I've always LOVED this city, and I'm so happy to find it's just as lovely to live in as it is to visit and watch on screen.

Eran: Heyo, I'm Eran, and I'm definitely the writer, because when I do art, people cry. I've been a roleplayer ever since I discovered the D&D Red Box around 1990, and it quickly became a passion, then a career. I've worked as a game translator, a professional game master for social skill development, gaming store owner, and probably a few other things, all with "game" in the title. Like Aviv, I'm from Israel originally but I moved to London around 2012 following my wife's career - she has a PhD in English literature, specialising in "London and the Fantastic". Yeah! I love nothing more than to explore new worlds, even though I'm usually the game master, which means my players get to do most of the exploration. Aviv and I share a love for high-action, light-hearted fun, and so we got to create a few octane-fulled narratives over the years, trying out various approaches and concepts.

Tell us more about Up to 4 Players! What inspired you to start it and what have been some of the highlights for you so far?

Aviv: Eran and I first joined forces about 13 years ago on V-Squared, a webcomic for the online video game magazine he was writing for and editing at the time. I'm still kind of amazed to remember that I actually got paid for drawing comics back when I was 21! We had a really good connection working together, a mutual sense of humour and very compatible way of looking at things. At some point, though, V-Squared had run its course and ended. Years later, we both itched to work on something similar again, and the idea for Up to Players was born. (It actually originated as a Stretch Goal for a crowdfunding campaign Eran ran for his roleplaying podcast, On the Shoulders of Dwarfs.)

We had a couple of brain-storm meetings, thinking about the structure of the comic and the main characters, and we decided to combine jokes about board games - a hobby we both share - and anecdotes about Israelis moving to London - which we both are. It was great fun to do a steady 3-panel (more or less...) comic together again, but after almost 150 strips we wanted to try some longer-form storytelling, and talk about our even bigger mutual hobby - roleplaying games. Thus Crystal Heart was born.

Eran: Since Aviv covered the history, I'll cover some of the highlights. Several of our strips got some global attention, thanks to being shared by the likes of Blizzard's Heroes of the Storm, Fantasy Flight Games, Czech Games Edition, and others. That was always exciting, watching the next-day figures in our analytics, but most of the time, they didn't translate to tens of hundreds of new followers - most people enjoy what they enjoy, and have no interest in next week's joke, which will be about some other game. Discovering that despite this we have a large enough fan base to allow us to open and maintain a successful Patreon page, THAT was awesome. We have nothing but respect to the people that seem to have respect for us, and I think that's a good relationship between creator and consumer. The next step was having a table at UK conventions, which is what we've been doing for the past year, and also definitely going to continue doing in the foreseeable future.

I have to say the illustrations in your webcomic are absolutely gorgeous, where did the look and feel come from and how has this developed over time?

Aviv: Thank you! A huge inspiration on my style back when I did V-Squared - and still today - was the webcomic Penny Arcade. I've always loved Mike Krahulik's character designs, extreme expressions and smooth line work, and it's been a highlight in my career when I recently got to work with Penny Arcade on Thornwatch! In Crystal Heart there is also a lot of inspiration from animated shows like Gravity Falls and Steven Universe: I am awed by how much atmosphere and personality they create with very simple, minimalist lines and beautifully balanced colours, both in characters and in environments. And always in my art there are Disney influences, because I spent my childhood mesmerised by all the old and new classics.

Eran: Aviv mentioned a lot of cartoons, and for a good reason. We not only use a cartoon-inspired art style, we also have cartoon-inspired character personalities, humour, and storylines. High-action, light-hearted fun! Also, in order to publish weekly instalments (first strips, now pages), the art style HAD to be simple. Even though we nowadays have a Patreon and sell some merch at conventions, we mostly use this money to pay for what we need to maintain the webcomic. Aviv is still doing this in her spare time!

In regards to time, how long would you say each comic takes to produce, considering both illustrations and writing?

Aviv: From the illustration side, it takes about 10 hours to produce a page (back when we did short strips it was more like 3-4 hours). I wish I could reduce it somehow, but I wouldn't want to sacrifice either the style and level of detail we established, or the "amount" of plot we manage to get into every page; since we post a new page only once a week, we want each update to be worth the wait. As far as burn-out goes, I think the fact that this is a weekly webcomic helps tremendously: every week we get to hear readers' feedback and know that there are people out there who enjoy what we do. It makes it much easier to keep going, rather than if we had to draw page after page and keep them under wraps for future publication.

Eran: Writing-wise, we both decide on the main plot for the current storyline, and then I start turning it into pages. I already have a feel for how much panels/pages each plot point is going to take, but it's a fluid estimation that changes as we progress into the story. Each page is pretty straightforward, taking about 45 minutes, with lots of revisions and some research (mostly into our own archive, to maintain consistency). I decide what plot and dialog we should have in every page, and then provide a general storyboard which Aviv then develops into the final layout. The work process between us includes several back-and-forths and has been tried and tested to perfection, which is insanely important in this kind of creative endeavour.

Of course, I couldn't interview you without talking about Crystal Heart. Elevator pitch time, what is it and why should we be interested?

Aviv: Eran, I'll let you answer that one fully because OMG I really need to get on Monday's page!

Eran: Crystal Heart is our ongoing storyline, a webcomic about four players (exactly!) playing a roleplaying game. We show what's happening in the imaginary world, with all the special effects, crazy shenanigans and cool characters that should be there, but we also show what's happening around the table, between the players themselves. We want to cover the full experience of an RPG, and that means in-play action but also off-play remarks, misunderstandings, and problems that arise naturally in these kinds of games.

The world of Crystal Heart is one in which people have stones for hearts, in a very literal sense. Some people can replace their heart with a Crystal, ancient artifacts from before recorded history, and thus gain superpowers! But also get a bit deranged. You see, the Crystal influences your personality, giving you strange quirks or new thought patterns. It's meant as a fun exercise for the players - remember, this is a setting for an RPG, not just "a fantasy world"; It must have RPG sensibilities. The player characters are Agents of the powerful organisation Syn, scouring the world in search of new Crystals.

When we switched our webcomic style and started telling an ongoing story about roleplayers, we obviously lost some of our readership, who liked our focus on board games. However, we didn't actually lose that many people, and at the same time, we gained lots of new ones, making Crystal Heart popular enough to have us consider publishing it as an actual game you can play. So that's what we're doing!

The concept of turning a webcomic about people playing an RPG into an RPG people can play is so meta. I love it. Let's talk about the game itself, when did this idea come about and in broad terms what is it?

Eran: We created CH for our own gaming group, many years ago, and played several awesome sessions in it. Ever since then it remained in our hearts, pardon the pun; I actually started considered making it into a Savage Worlds setting several years before we even had the comic. There's a ton of roleplaying potential in the basic concept, of having interchangeable superpowers that also influence your personality, and also, I never got to tell the REAL STORY, the secret history that will eventually be revealed in the comics, so I was keen on finding a way to publish it in some form. Then the comic came, and now, the game follows suit.

In CH you play as Agents working for the powerful organisation Syn, sent to find and retrieve the ancient Crystals that are scattered all over the continent. If this feels like the plot for an anime-inspired video game - good! In the wild, the Crystals are feral and unpredictable, creating various dangerous magical effects. Syn developed a method that allows its Agents to implant "tamed" Crystals, and turn these effects into tools and weapons. The only problem is, the Agent has to give up their own heart, and the Crystal which replaces it comes with some emotional baggage. This concept, while unique, is also pretty straightforward, which is very important to us - we wanted the comic to be approachable and we want the game to be accessible, which is why we've released a free Starter Set with most everything one needs to play.

You've chosen to power the world of Crystal Heart with the Savage World ruleset. Why is this ruleset special and what makes it the perfect fit for your RPG?

Eran: Savage Worlds is advertised as being Fast, Furious Fun, and it really is. That's the kind of comic we wanted to have, full of quick actions and pulp-inspired twists and turns. SW works very well with unusual settings - it has about a dozen official settings, all of them weird in some way! Also, and that's super important, it's an easy system to explain and understand - you just roll a die and need to get a 4 - because we had to explain the rules as we were telling the story. It's a story about people playing a game, so the game is one of the main characters.

Originally we were thinking of using a more narrative-based system, like Fate, or a Powered by the Apocalypse game. These systems help the players create an awesome story simply through the process of being played. After some consideration though, we realise that WE are the ones that need to have control of the story, not the rules - what works around the table doesn't necessarily work for stories being told ABOUT what's going on around the table. We also have only good things to say about the owners of Savage Worlds, the people at Pinnacle Entertainment Group, who support their community (and us) very well.

The webcomic has built a rich narrative story, so what were some of the most important things you wanted to bring across into this game?

Eran: Oh, what a question! Most of the things we now bring into the game were established during the first few months of the comic, because Nadav, the game master, had to make some decisions when creating the campaign he's running (that is, we had to make these decisions, so that his game will be realistic). So, for example, the fact everyone is working for a powerful, mysterious organisation is a big deal both in the comic and in the actual game. We've replaced money with Requisition, meaning that if you want something, Syn will provide it, but you need to prove yourself (raise your Req points!). We created a reputation table, to help game masters decide on how people react to the player characters; it's called Everyone Has an Opinion About Syn. We add rules for special teamwork, training, rival Agents, Syn facilities, and more.

The second important aspect we import from the comic is the themes. Each Crystal has a theme, each Land has a theme, campaigns should have a theme. Themes help keep a tight narrative, they guide you toward a specific path and keep you from wandering off, and that's a powerful tool in any improv environment and especially roleplaying games. We explain all the themes and also give some guidelines and rules as to how to use them.

Finally, we wanted to bring the colourfulness of the comic, both literally - the book is going to be very colourful, I mean, just look at the cover art - and figuratively, by having rich, diverse populations. The entry for each Land, for example, focuses on what makes it different from the others. Everyone has politicians, sure, but in what way are Bogovian politicians different from Zingamaian? (the former lie to the public, the latter poison their enemies). We'll also have characters from many colours of the rainbow, many genders and races and whatnot. It might seem like a game about Crystals, but it's actually a game about people; and there sure are a LOT of kinds of people in the world, so we'll have them in the game as well.

A big part of the world you've built is shown through the art. How does the game continue that and what differences are there if any?

Aviv: We plan for the book to have A LOT of art in it. Probably more than the average Savage Worlds setting book, because as you said - that's a big part of the world. The main difference to what we've been doing so far is that it's not going to be sequential art, but individual illustrations that support and illuminate the lore, mechanics, and world building; so I am free to invest more time and energy in design, concepts and making every bit of this world as awesome as possible, because I don't have to worry about re-drawing these things for the next 30 comics pages! In terms of style, I think we've established a pretty strong artistic language through the comic and several other pieces of content we've created for our patrons (some of which would become available during the Kickstarter), so I don't see it change much for the setting book. It's also fairly unique in the world of RPG art, which I'm quite happy about!

Your Kickstarter for Crystal Heart launched on November 20th, so finally for anyone still on the fence why should they back?

Aviv: For those who enjoy Savage Worlds for its pulpy, fast, furious and fun adventures, I think Crystal Heart does all of that with a nice shiny crystalline gleam! It's a setting full of colour where so many settings nowadays go for the dark and gritty. There's plenty of drama and darkness to be found in Crystal Heart for sure, but you can also play it super lighthearted and fun (I have recently GMed a short one-shot where everyone ended up dancing to the beat of a disco-ball Crystal in the middle of a jungle).

For people who haven't played Savage Worlds, it's a fun, fairly simple system to learn (we actually explain the basic rules to it in a 2-page comic), and it's just finished very successfully Kickstarting its newest edition, so it's a good jumping-on point. And Crystal Heart is one of the first settings that will be be available for the new edition, so - join Syn, exchange your heart for a superpowered Crystal, and get adventurin'!

Endogenesis: Art in Board Games #47

Star charts have an amazing aesthetic that feels foreign and esoteric, but mesmerizingly detailed. Combined with the use of astronomical symbols, I sought to create an art direction that gave the sense that you're peeking into this whole other alien universe through the perspective of its inhabitants.

Editors note: Welcome to another in my series of interviews looking into Kickstarter projects. Endogenesis (from David Goh) is well into its campaign and currently at over 1200% of its very modest funding goal. Upon seeing the Kickstarter page I couldn't help but be impressed by the production quality of this a first-time project so I'm really happy to find out more. The Kickstarter is live until 7th September so if you are curious I recommend you go take a look.

Hello David, thanks for taking the time to speak to us. Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Sure! I'm a freelance art director hailing from Singapore, and I'm 30 this year. I grew up being surrounded by gaming — as a teenager, the medium of choice was video games, from old-school RPGs like Chrono Trigger to thriving new releases then like DotA. But in the last decade or so, I've been slowly steered towards tabletop gaming, primarily due to its social nature. There's just something about sitting down with a group of friends at board game night that video gaming just isn't able to replicate.

As for designing games, I've always wanted to make them since I was 15. Regardless of medium, I believe that games are the next greatest art form, and that's why I'm obsessed with them! I just enjoy taking them apart and studying them, and try to understand how some games can be so engrossing, and others evocative. The idea that games are really just a collection of rules, visual aids and predictable logical outcomes that combine to captivate the human mind with a compelling experience is just mind-blowing, and still is to me.

My first foray into tabletop game design was with a fan-made card game called 'Final Fantasy Boss Battle.' It was created as a birthday present for my wife, made quickly in 2 months as it was intended to be less of a working game and more of a really cool looking gift. We played a couple of games with our friends at board game night, and while the game was clearly unpolished and a little frustrating at times, it was actually fun for a few sessions.

Seeing how I had created something that brought enjoyment to the game night table, I felt inspired to keep creating, if only to make games that my friends would enjoy. And so I did! Over the next 9 years, I'd designed prototypes to bring to the table. Many were pretty much trash, while some had potential. One other project that went beyond the table was 'The Award Winning Game', which I worked on as part of a team of two. While we did bring it to Kickstarter a few years back, a combination of inexperience and logistical difficulties led to the project not succeeding, so we published it via The Game Crafter instead. Having a group of friends to test out game concepts has been such an amazing learning experience, and I'm glad to have such patient friends!

Looking at the present, can you describe your current Kickstarter game to us and what makes it interesting?

Endogenesis is a competitive card game that features free-for-all combat, which means it focuses heavily on direct conflict! What I think makes it interesting is that the gameplay is designed to be highly customizable and interactive. Everyone starts off with the same blank slate, but as the game goes on, you build a customized power set with the Skill cards that you're dealt with. If you like the experience of building a character that starts out weak but incrementally grows until you're a behemoth of cosmic power later in the game, then you'll enjoy Endogenesis!

While the round and turn order are quite structured, what you do during your turn isn't. You're given freedom on how you perform actions, both in their order and frequency. This includes using Skills to attack others, equipping new Skills or leveling up your character with Shards (which are a bit like stat points). With a bit of creativity, you can pull off really powerful combinations of actions, but at the same time, just a bit of miscalculation can cause your plans to fizzle. There's also an element of intrigue, where you can interact with the active player's turn with Reaction Skills, which are hidden, allowing you to set up traps when you know what a rival player is planning.

Because of my background in video games, a lot of inspiration came from that medium. A key point of influence for Endogenesis was from a custom game mode from DotA called DotA LOD, which is the precursor to the Ability Draft mode in DotA 2 now. Each session of the game sees you crafting a character from a random pool of abilities, effectively building your own synergies and combos. My goal was to recreate that experience in the tabletop medium, and Endogenesis was the result of that attempt.

How long have you been working on this game? What made you launch the campaign now?

I've been working on Endogenesis for a little over two years. Like all my previous designs, Endogenesis started out as a prototype I brought to game night, with the intention of creating something my friends would enjoy. However, the response to Endogenesis was much better than usual, so I decided to focus more effort into refining it, eventually bringing it beyond my circle of friends to other board gamers, and later on to blind testers.

I would say that Endogenesis is the culmination of a few concepts I've been wanting to try out with the tabletop medium for a long time. Quite a few prototypes died along the way before I arrived at Endogenesis, and I feel that after a few hundred playtests and 6 major revisions, it's finally ready to be released. I've witnessed a lot over the course of testing the game; the intensity over a very close battle, the excited spark in a player's eye as they execute an elaborate game-winning combo, and their rage at having said combo be completely countered by a well-placed Reaction Skill or Wonder... I'm excited to let gamers around the world try out the game, and see what experiences they encounter as well!

Where did the world and lore of Endogenesis come from and how does that feed into the player experience?

Prior to working on the world and lore of Endogenesis, the gameplay came first. And a key part of the gameplay was the existence of Skills that would come from different categories: Cosmic, Mythic, Entropic, Organic and Mechanic — all of which meant to be very different from each other. This was the first spark that led to the direction we took while building the lore; given how different these categories were, we needed a setting that would serve as a plausible container for all of them. Thus the idea of a universe in which beings explored other planes of reality was born.

As for why the setting takes place in a tabula rasa universe with alien beings, I think that came from my love for creation myths in general. Combined with the challenge of building a setting that would see the clash of different planes of existence, I saw the opportunity to redefine the entire tone of the story by building it ground up with a whole new creation myth.

A big part of what Endogenesis offers is a "power fantasy." The journey you take starts you out as being weak, but you incrementally grow stronger and stronger until you're inches away from literal godhood. This lore feeds into the player experience by creating an epic setting that players operate in, so as to make that power fantasy feel magnified to cosmic proportions!

This lore also seems to have fed into the artwork and style, showing a mixture of astronomical symbology crossed with arcane monsters. What were some of the most important factors in making you take these visual choices?

As a huge fan of RPGs, I find world building to be incredibly fun! I also had two writer friends (Ryan Mennen and Sathya Seth) who were excited to lend their expertise, and as such we pushed ourselves to go as deep as we could with the lore behind Endogenesis.

Having a detailed setting to work off helped tremendously as I was creating the art direction of Endogenesis. One of the most important considerations was trying to decide how the universe would look. How does one portray an entire universe feels completely alien from ours? This wasn't just in a different galaxy — it was an entirely different reality, with its own physical rules and destiny.

To that end, I decided that the simplest way to do this was to avoid trying for a realistic portrayal of that universe. Instead, I imagined how the inhabitants of the universe would have illustrated their visions of how they perceived their surroundings instead — not unlike how early humans would make rudimentary cave paintings of their environments to store information. In doing so, the Endogenesis universe could actually be made to feel even more alien, since an exact representation of that reality is never seen.

With that direction in mind, I researched the ways humans have of recording observations and information across the ages. I eventually settled on star charts and runic symbols as a key visual reference. Star charts have an amazing aesthetic that feels foreign and esoteric, but mesmerizingly detailed. Combined with the use of astronomical symbols, I sought to create an art direction that gave the sense that you're peeking into this whole other alien universe through the perspective of its inhabitants.

How did playtesting and community feedback guide you in this project? What lessons did you learn and was there anything that surprised you along the way?

Besides the obvious improvements that heavy playtesting brings to a board game, the feedback I've gained also revealed a lot about me as a game designer, as well as the blind spots I didn't know I had. As someone who's still very new to the scene, this was especially important for my growth.

I would say that one of the biggest changes in my mentality as a designer was towards the inclusion of catch-up mechanics. In the early half of the game's development, I was rather against including catch-up mechanics. For some reason, I felt that doing so might make the game feel better for casual players, but worse off for experienced ones, and that that trade-off simply wasn't worth it. But on the advice from a few blind testers and early reviewers, I decided it was worth a shot.

And I was so glad I did. The game became a lot more interesting as a result, because now gaining power comes at an increased potential cost. The more you have, the more you stand to lose, so you have to consider carefully how you go about gaining power. Being able to snowball without much thought might give you a fleeting sense of power and invincibility, but it's nowhere compared to the intensity of having to watch your back. On the flip side — for weaker players — the less you have, the less you stand to lose, so you can be more proactive and fearless in pursuing opportunities, therefore giving you more agency to better your situation. I was so surprised at how much of a positive change a few catch-up mechanics brought.

You collaborated with a number of people to help create the look and feel of this game. Who was involved and what did they bring to Endogenesis?

For the creation of the Endogenesis myth, I worked with Ryan Mennen and Sathya Seth. Both of them are writers, and have unparalleled knowledge when it comes to pop culture and mythology. They're both also my closest friends and amongst the first few to try out Endogenesis, so it just made sense to work with them.

For the creation of the monsters from the Realm of Chaos, I worked with an illustrator named Yang Shao Xuan. These Monsters were inspired by Lovecraftian horror — they're creatures that emerged from the source of pure entropy, and are powerful enough to serve as threats to cosmic beings. Shao Xuan was a great fit for this, given his keen eye for detail and skill for portraying anthropomorphic characters. His monster illustrations were very flavourful and distinct, which was no easy task given that they're just silhouettes!

Lastly, being a project made in Singapore, I sought to work with as many Singaporean talents as possible for the needs of the project. Not that there's anything wrong with looking abroad for help — I just wanted an opportunity to showcase the works of local talent!

I think it's really important to support your local communities when you can. So what should people be doing to make them a part of their projects?

The best way to start is to definitely go out there and make connections. It's never too late to start, and it's incredibly easy to do so. Go to flea markets, artist alleys, youth events and meet people. Join groups on Facebook where artists gather and interact with them. Find out they care about, and see how you can help. Another thing you can do is to look up old friends, school mates and see what they're doing right now, and see how you can trade expertise with them.

Do you have any advice for people looking to launch a Kickstarter game?

I'm still in the midst of my first Kickstarter, so I kinda feel ill-equipped to give advice. I can, however, speak from personal experience and talk about the things I felt I could've done better.

While I did a great deal of preparation work for the campaign, the campaign went off in a direction I never dreamt of, which led to me feeling like I was in catch-up mode for the first week. Initially it made me wonder if I didn't do enough prep work, but looking back now, I think that it's just down to the simple fact that unexpected things happen. Especially if it's your first time — no amount of discussion with other creators or reading of articles can fully prepare you for how people will respond to your work. So I'd say do as much prep work as possible, but expect that the unexpected will happen.

Another thing would be to not underestimate how difficult it will be to say no. It's one thing to say no to a stranger, it's another to do so to someone who's investing in you and your vision. The latter takes a lot more out of you. Saying no is something I feel like I've been doing fine at so far, but I just never expected that it would be so difficult. In hindsight, I suppose I should've been more prepared (though, how does one really prepare for that?!)

That's all I have at the moment, I'm sure I'll have more thoughts and ideas once I'm further along the campaign.

Are there any artists and designers in the community whose work you’re inspired by?

This is probably something you hear a lot of, but I'm a big fan of Jamey Stegmaier. His approach to crowdfunding, customer engagement and competence as a game designer just wows me. I think it's safe to say that many board game designers (including myself) would not have found success on KS if it weren't for his articles.

I'm also just blown away by Daniel Aronson and the work he did for The Isle of El Dorado. I came across his campaign very late, but I was just wowed by the game's level of polish and how the campaign was designed. I've never seen anyone use pre-1900 art in such a way that looks so attractive and modern. And as someone who had to build most of the art in Endogenesis single-handedly, I'm amazed at the amount of resourcefulness Daniel had in conceptualizing his game's art direction.

Lastly, there's a game designer who frequents the game design forums on BGG by the name of Jeremy Lennert (Antistone). Every time I come across a post by him, I stop and take the time to read it carefully. He's so incredibly knowledgeable, insightful and eloquent, whenever I read his stuff for just 5 minutes, I feel as though I've squeezed in an hour of game design classes. Absolutely riveting.

What are you currently reading, listening to or looking at to fuel your work?

I'm watching Psycho-Pass now, a cyberpunk anime that's mind-blowingly good! If you haven't guessed, I'm a big fan of sci-fi :D I'm also doing a playthrough of the entire Dark Souls series with my wife. Dark Souls is a huge source of cognitive dissonance for me — there are so many design choices I disagree with in the game, and at times I'm very frustrated by it... and yet, it's brought about some of the most memorable and enjoyable moments I've encountered in my life as a gamer. I recently played a game of Rise of Moloch too, and while I didn't enjoy the heavy usage of dice combat, I find the asymmetric gameplay to be very attractive. I'm hoping to get back to it soon (as soon as things with the campaign get less crazy!)

Finally, if we’d like to see more of you and your work, where can we find you?

You can check out Endogenesis on Kickstarter.

My personal portfolio can be seen at http://www.awesome.sg and my illustrations at http://www.hyperlixir.com.

(All images supplied by David Goh)

Josh Emrich: Art in Board Games #46

A memorable color signature can really help a game stand out. Like any design decision, color should always point towards the story or experience you think will engage the audience. I always want to find colors that are unexpected and complex, but functional and serve the story and setting.

Editor’s Note: When I created this site, Josh Emrich was among the first people I contacted. Their work is exceptional, and you seem to agree, voting Campy Creatures in the top 10 for the Best Board Game Art of 2017. Enjoy the interview, I can’t wait to see more from this talented studio.

Check out the interview archive for more great insights into board game art.

Hi Josh, thanks for joining me! For our readers who aren't aware of your work could you tell us a bit about yourself and what you do?

For as long as I can remember, I always wanted to be an artist who made things other people could enjoy. Which is crazy because I grew up in a blue-collar family in the industrial midwest USA. My parents had no artistic background and I had to explain to them what makes good art and why I was doing a particular thing. Many artists aren’t great at articulating their ideas, so I credit my parents in helping me develop this skill.

When I went to study art at university, I had a hard time picking one thing — I loved it all — but ultimately studied visual communication design because it touches multiple disciplines — graphic design, industrial design, illustration, etc — with a commercial or strategic purpose. I have since worked as a creative director, designer and illustrator at brand design agencies, eventually becoming a founding partner at a design firm. Eventually, running a firm became a strain on my family, and I got burned out. My wife Katie is also an artist and together, we have four artistic kids. We decided to simplify and make design and illustration the family business. In 2013 we created Emrich Office, a brand design agency that specializes in creating identities and packaging for craft beer and spirit brands. We work from home in a 1000-sq-ft studio filled with vintage action figures and midcentury furniture.

Because we work with a lot of craft breweries, these clients can’t all look the same, so we have had the opportunity to develop and master new art styles with every project. This unique skillset is what brought us to the game industry.

When beginning to work on any new project what are the first few things that you do?

As a movie buff, I like to think about my projects like a film director thinks about a film — the story is the most important thing. If you don’t have an interesting story, you don’t have much to stand on. It’s something I really try to draw out of my clients. The first step is identifying the audience and crafting a unique message that’s engaging. The next step is fleshing out our guiding principles: what world this story takes place in, who are the characters, and what will the experience be? Like a method actor, I have an obsessive personality and will get really immersed in the research — watching any relevant films, reading books, studying history, finding forgotten illustrators, listening to music, etc. Because most of the story is told visually, Pinterest has become a great resource for collecting inspiration and sharing it with my clients.

This creates a foundation of intentional and well-articulated rationale for everything I do. It shows my clients that my creative decisions are focused and not arbitrary, ensuring that I’m delivering something that fulfills their purpose.

Your first board game project was the absolutely gorgeous Campy Creatures. So how did you get involved in that and what do you remember about it all?

Let me start off by saying I’m new to the board game industry. The first things that struck me is that much of the game art (in the industry) shares a similar formula and style. There’s a large emphasis placed on illustration, but often the graphic design is not very well integrated or well executed. Much of it is not very sophisticated. This creates an opportunity for game publishers and artists to break some stereotypes and attract new people who are normally turned off by board games into the fold.

I put a lot of work into research and understanding the project before I dive in. I don’t like presenting tons of options. I think that’s a cop out — like throwing a dart at the wall. I want to have everything worked out before I present anything and nail it on the first go. So I watched tons of the old Universal and Hammer horror films and collected vintage posters in Pinterest. I wanted to honor those films and characters while making Campy Creatures it’s own thing — knowing the exact right points to adhere and deviate.

Keymaster Games, the publisher of Campy Creatures, is run by two graphic designers, Mattox Shuler and Kyle Key, who really understand what it takes to create a game with street cred and still have a broader appeal. They are willing to take risks and invest in production details. They also encouraged me to share my in-progress work on social media to help generate interest in the game, which is a different experience for me. Usually, my clients want me to keep things tight-lipped until the beer is released. It became a little focus group and the reaction was really positive so it gave me a lot of confidence in my approach.

From this experience, I am now hooked on board games and I’ve found a great partner in Keymaster.

You make a good point about board game visuals largely playing it safe. When you talk about taking risks, what stylistic risks did you take with this game?

I guess I don’t see it as taking risks as much as finding ways of differentiating to stand out. Before I started working in board games, I was a brand consultant. Coming from that perspective, it’s a bigger risk to blend in. For Campy Creatures, we could have made it look either very cartoony or like the standard concept art style that pervades the game industry now. Instead, we really embraced the classic horror movie poster vibe, not only with pulpy illustration but also with the type.

Campy Creatures was Keymaster's second game and they really wanted to capture the feeling of classic monster films. Many of the original movie posters from this era were created by commercial artists who could not only illustrate but could also integrate lettering and type. These days, illustrators and designers tend to be more specialized and often work separately under an art director. This can lead to some mixed results where the illustration and type are not working together. In order for Campy Creatures to feel authentic, Keymaster needed an artist who could work like an old-school commercial artist integrating both illustration and type. Mattox had seen some pulpy, b-movie-inspired beer labels that I had designed and illustrated and thought that I could pull it off.

You also mentioned the need to inject a distinct character into the creatures you drew. So what is the trick to creating memorable and captivating characters in your work?

One of the major points of deviation was that many of the original horror monsters tended to be male, so we reinterpreted several of the creatures as female. I always try to push past a general trope by adding a humorous detail or element that allows the viewer to start imagining a larger story around the creatures. For instance, the Invisible Man in Campy Creatures has a Film Noir vibe and is in the process putting on leather gloves. Not only does this create a threatening posture, but it implies that he’s about to commit a crime. Hopefully this sparks the viewer’s imagination and they begin to fill in the rest of the story.

The only creature that received any major revision was the blob. A blob by nature doesn’t have any defining features, which creates a difficult problem when it needs to be a distinct character. My initial thought was to feature a melted victim within the blob to give it some structure, but that was a little too scary for younger players. We ultimately decided to give the blob an eye and to suggest a more defined character.

One aspect I love about your games is the very distinct color palettes you use. How do you use these colors to set the tone in these games?

A memorable color signature can really help a game stand out. Like any design decision, color should always point towards the story or experience you think will engage the audience. The colors for Campy Creatures are rooted in classic movie posters and pulpy lighting, while the colors for Caper are inspired early 1960s European fashion and interior design. Some things that I think stand out in our work is our use of color on Caper. It’s offbeat and sophisticated, using pink, mint, and metallic gold, evoking a Wes Anderson aesthetic. I never want to use a “standard” color palette — basic red, blue, green, etc. I always want to find colors that are unexpected and complex, but functional and serve the story and setting.

Speaking of Caper, can you tell us a bit about its theme and how that developed?

Caper was designed by Unai Rubio and was originally published as “It’s Mine” by Mont Taber in Europe. When Keymaster approached me about helping bring this game to U.S. audiences, I had two suggestions. First, there are a lot of games set in Europe, but if we pick a specific time period, that will help build an interesting world and refine our design choices. We decided 1960-something Europe would be a fun place for players to visit, evoking the great heist films from that era like Pink Panther, To Catch a Thief, or The Italian Job. Second, the characters and gear really help set the tone, so they need to be eccentric, humorous and interesting. The best way I could describe what my approach would be to Keymaster was “what if Wes Anderson directed a Pixar-animated heist film?”

Did your experience working on Campy Creatures change your approach when it came to Caper?

Not really. The two games are completely different, which is refreshing for me. I get bored easy, so I really like charting new territory. The characters in Caper were less defined so I had an opportunity to explore my own ideas. There’s also a lot more art in Caper — 24 thieves, 24 gear items, and 23 locations — so I had to work quickly, which helped inform the vintage gouache style I used to render the illustrations.

What advice would you give to anyone wanting to work as an artist?

Art is not just copying something you see or letting your imagination run aimlessly. To me, it's visual communication and the best artists are able to cut through the clutter and deliver an engaging message. Obviously, you need to develop your skill and technique through constant learning, experimentation and practice. But the most important thing is being able to empathize with others so that you can speak to them. Lastly, you can’t be drawing all the time — you must have your own experiences too so that you have something of value to share.

What are you currently reading, listening to or looking at to fuel your work?

I’m sort of between major projects at the moment, but I’ve been reading the Wildwood book series to my kids during their summer break. The series is written by Colin Meloy of the Decemberists and illustrated by Carson Ellis — part of the same team that developed the beautiful game Illimat with Keith Baker. It’s inspiring to see other artists and storytellers that do not confine themselves to one discipline!

Do you have any current projects underway, or coming up that you’d like (or are able) to tell us about?

Umm…I hear there are more Campy Creatures in the works! And Emrich Office, the brand design and illustration practice that I run with my wife, Katie, is turning 5 years old. We are going to partner with one my favorite collaborators, Bottle Logic Brewing, to produce a limited release beer to celebrate. We hope to raffle the bottles off in the Fall to help raise money for arts education.

Finally, if we’d like to see more of you and your work, where can we find you?

Instagram is where I post my most recent collaborations. You can follow me @emrichoffice.

(All images courtesy and copyright of Emrich Office, 2018)

Ryan Laukat: Art in Board Games #45

There's an inner child in me that guides almost everything I work on. The sense of wonder I had when experiencing new worlds when I was young is one of my biggest reasons for creating games and settings.

Editor’s Note: There are a few artists whose work inspired me to start this website. Ryan is one of them. His work features in a number of board games in my collection, and whenever I play them, I feel immediately drawn into worlds that feel magical and inviting. Enjoy our chat!

Check out the interview archive for more great insights into board game art.

Hi Ryan, thanks for joining me! For our readers who aren't aware of your work could you tell us a bit about yourself and what you do?

Hello! I'm a board game designer and illustrator. I've been lucky enough to work in this industry for around ten years. I started as an illustrator and then founded Red Raven Games so that I could publish my own designs. Some of my games include Above and Below, Near and Far, and Eight-Minute Empire. I live with my wife, Malorie, in Salt Lake City, Utah, right up against some beautiful, snowy mountains, and within two miles of where I grew up! We have a daughter and two sons.

Red Raven Games has become synonymous in the industry for combining great art with captivating worlds and stories. When you're creating a game what is your general thought process? Where do you start?

My obsession with creating games started when I began inventing tabletop role-playing games as a teenager. I loved to create worlds to explore and creatures to inhabit them. So naturally, that influences how I approach most of my board game designs today. When creating a game, my motivation is usually to build a world and use the game mechanisms to allow players to explore it and experience it. I think about who the players will get to be in the game, and where they will go, and start there. I think it helps create a more immersive experience.

Last year you successfully kickstarted Empires of the Void 2 the follow up the 2012 original. What can you remember about that time (2012) and what made you want to return to this project?

I'd wanted to revisit the game for many years. I actually made many redesigns of the original game but never published any of them. I wanted another shot at the setting because I felt my skills as an illustrator and game designer had improved. Of course, Empires of the Void was my first published game. I'm proud of what I accomplished, but there certainly were things that I didn't do quite right. The rule book in that first game was not sufficiently clear and left too many things unexplained. The trading did not pan out as well as I had hoped. Some players left the game with a frustrated feeling because of a multiplayer direct conflict problem where two players can gang up against a third, leaving no way to catch up. I wanted to solve these and many other problems, and so I attempted it in Empires of the Void II.

In terms of the illustration, when you worked on Empires of the Void 2, how did you aim to develop the originals aesthetics into this sequel? What have you learned about graphic design and art since the original and how did that impact your choices?

My goal this time around was to create something a little more on the realistic side when compared with, say, Near and Far, and indeed, the original Empires of the Void. I wanted to make a beautiful space map like the original had, and of course many of the of the original aliens and planets, but with an updated vision that I felt would be more immersive. I looked at a lot of hard sci-fi art, especially the covers of books from the 60s and 70s. This meant painting with more subdued tones than usual and experimenting with new brushes.

You are arguably best known for your work on Above and Below and it's sequel, Near and Far. So starting with the original, how did you create this world and was there any inspiration you drew from in developing it?

When creating Above and Below, I actually sketched the cover before I even designed the game. That sketch worked as a compass for me, and I designed the rest of the look and the game mechanics around it. I was trying to pin down the feelings and memories that I had playing Super Nintendo games as a child, and that helped me build the friendly, colorful setting. At the time I was also very interested in making my games look as natural as possible, letting the art easily incorporate symbols or information, rather than have obvious graphic design boxes to keep art and information separate.

So thinking about that first sketch of the box cover, how did you get from that initial idea to the game we see today?

I took that sketch and taped it to my computer monitor, hoping to get the same sort of feeling that was in the sketch. Sometimes it's hard to replicate the feeling that is present in a thumbnail or sketch, and it can be pretty frustrating. Thankfully, this time, I threw down the colors quickly and it was like a seed sprouting into a huge, blossoming tree. The Above and Below cover took around four hours, and it didn't change too much after that. Sometimes I repaint the covers for my games multiple times (like with Near and Far), but this time, it felt right pretty much from the get-go.

I used a lot of blue and green, especially on the box, as a message to players that the game is pleasant and inviting. Just as important is the chalky brushwork and painterly style, which is meant to remind the viewer of a children's book. It says, "There's a story in this game."

I paint using a Wacom tablet, but I've learned to watch the monitor so I don't have to use the tablet's screen (it's much faster and more efficient for me if I don't have my hand in the way of the painting). My method has changed over time, but it's been pretty consistent for the past five years, besides updated brushes and the way I choose colors. I paint exclusively with Photoshop, and I'm pretty particular about having the right brushes, shortcut keys, and layout.

When you came to work on Near and Far, how did you aim to base it in the same world (as Above and Below) yet still take the player new places?

I made sure to keep the painterly style and chalky brushwork, but the yellow and orange tones are more associated with risk, exploration, and adventure. Western movies and art were a big influence on the look of the game. At the same time, people need to know that this is in the same universe, so animal races play a big part in the setting! I also decided to include some inked drawings instead of detailed renders on some components, such as the World Cards and the Treasure Cards. I feel like this matches the "wild frontier" feel I was going for.

You talked about nostalgia towards childhood games, so how important has it been when illustrating your games to create worlds that are inviting for all ages?

There's an inner child in me that guides almost everything I work on. The sense of wonder I had when experiencing new worlds when I was young is one of my biggest reasons for creating games and settings. And with my kids, it's like I get to experience that sense of wonder all over again as they dive into books and games. A common inner thought I have is: Would 10-year-old me get excited about this?

As someone who has experience working in all areas of a games production what advice do you have for designers, publishers and illustrators to help them successfully collaborate?

Good illustrators are in this business not only because of their skill with a brush and their time spent honing their craft, but also because of their imagination and ideas. A good publisher and designer will give some creative liberty to the illustrator and not be too picky about how every little thing should look. Of course, for me as an illustrator, I want tons of creative freedom and it's hard for me to get interested in a project if I don't have it. Any good collaboration is going to require some give and take on everybody's part though. One thing I'm still learning is that I need to listen to all suggestions and know how to look through another person's eyes to see the project in a different light. What I might prefer personally might not be the best thing for the game.

Upcoming release from Red Raven Games, Megaland, is the first to have your partner Malorie as co-designer with yourself. Can you tell us a bit more about how this came about and what effect that had on the creation of the game?

It was a lot of fun designing a game together, but truth be told, Malorie has always been very involved in my game design projects, so it was only a slight change in dynamic. It didn't start out as a co-design. I was trying to design a light, push-your-luck game, but nothing was really working out. Malorie helped me solve mechanical problems with new ideas. We both have strong opinions about what works and what we like, so there were moments when we had some strong disagreements about this design. But I think that kind of thing is the forge fire that gets the design where it needs to be. I'm sure we'll do another co-design in the future.

What are you currently reading, listening to or looking at to fuel your work?

I've been reading Homer's Odyssey and The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas. Reading the Odyssey has been especially eye-opening and enlightening. It has an amazingly timeless quality. I've also been playing Pillars of Eternity, an excellent successor to the Infinity Engine games I enjoyed so much as a teenager.

Finally, if we’d like to see more of you and your work, where can we find you?

You can follow me on Twitter @ryanlaukat. We also post lots of photos of our games on Instagram @redravengames.

(All images provided by and copyright of Ryan Laukat and Red Raven Games)

Ian O'Toole: Art in Board Games #44

From the perspective of the work that I produce, the gaming industry allows the rare opportunity for me to create a complete product. For most of the games I work on, everything in the box, and the box itself, is designed by me (apart from the game itself of course!), and that level of ownership is pretty rare.

Editor’s note: This week I'm joined by one of my favorite creatives in the board game industry. He's been involved in some of the best-looking games of the last few years, proven when he grabbed the top 2 places in your Best Board Game Art of 2017 vote. Enjoy our conversation!

Check out the interview archive for more great insights into board game art.

Hello Ian, thanks for taking the time to speak to us. Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Sure! I was born in Ireland, where I grew up, received my education and met my wife, Sarah. We moved to Perth in Western Australia a little over a decade ago and have since had two children. I still have not acclimatized to the heat.

I read a lot of comics growing up, and my artistic development was always directed by that. I can’t remember entertaining the idea of doing anything else. When it came time to go to college I decided on Graphic Design because I knew there was a clear career path there, I could leave college and get a job. Fine Art was a little more nebulous, which didn’t entice me at all. I’ve worked as a graphic designer/illustrator for my entire professional life, in a wide variety of roles and industries, including marketing, advertising, packaging design, publication and spatial design.

Mysterium Poster - part of the BoardGameGeek Artist Series

For the past five years I’ve worked for myself, and board games have grown to occupy almost the entirety of my workload. This allows me to work at home which is ideal for me, giving me flexibility as well as the opportunity to see my kids more during the week.

I’ve always been a gamer to some degree, and played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons when I was a kid, as well as Games Workshop 40K games. I started playing modern board games about 9 years ago, when a friend bought me Catan, and shortly afterwards Dominion. I found a local gaming association and my interest in the hobby exploded from there.

As regards other hobbies, I really have very little time. I read when I can, and play guitar intermittently, but it’s mostly gaming.

The Gallerist

So how did you first get involved in making board games?

When I decided to work for myself, I reached out to the community on Boardgamegeek.com in an effort to diversify my client base. At the time I was working mainly in designing exhibit booths for petroleum companies, so I was hoping for something a little more fulfilling to work on. That got a bit of interest, and I ended up working on a few games. Some were very small Kickstarters, like Mage Tower, for which I only created a small part of the artwork, and others were full board games such as Fool’s Gold.

I quickly realised that having skills as both a graphic designer and illustrator set me apart from a lot of others in the industry. Publishers were very happy to hear that I had years of experience working with printers and manufacturers, so I already knew all of the ins and outs of setting up punchboards, box dielines etc.

Escape Plan box art

At some stage early on I wrote to Vital Lacerda, one of my favourite designers, about some of his upcoming games, as I was considering dabbling in publishing at the time. That didn’t work out but he did need artwork created quickly for The Gallerist, and asked if I’d like to take a look at it. The Gallerist ended up being one of the games that most people know me for, so that was really down to luck, and being proactive in trying to create opportunities. It has led to a very fruitful working relationship with Vital, and we are just now completing our fifth game together, Escape Plan.

Another such lucky opportunity was meeting Martin Wallace at PAX Australia, and joining him for a playtest of Ships. During the game we chatted and I told him about some of the work I’d been doing, and he asked if I’d be interested in working on the second edition of A Study in Emerald, to which I quickly said yes!

Working in games professionally also afforded me the opportunity to attend the Spiel in Essen in 2015, which would otherwise have been prohibitively expensive. That was the year that I got to see most of my games for the first time, as coincidence saw a few of them being released there. It was the first time I saw The Gallerist, A Study in Emerald and Fool’s Gold in the flesh, and also got the opportunity to meet a lot of designers and publishers, so that was a big year for me.

A Study in Emerald

Having stepped into the board gaming industry from a different background, what do you think the key differences are in how the work is created?

From the perspective of the work that I produce, the gaming industry allows the rare opportunity for me to create a complete product. For most of the games I work on, everything in the box, and the box itself, is designed by me (apart from the game itself of course!), and that level of ownership is pretty rare. It’s also the perfect industry for my particular blend of skills, which have struggled to find equal footing in other projects. Here, graphic design and illustration are both of very high importance.

Looking more widely at the industry itself, there really are no standards of any sort because it’s so young. Every publisher handles things differently. This can be especially apparent when it comes to discussions about licensing and contracts. It very much feels like it’s driven by passion rather than profit at the moment, and I think there are some growing pains on the horizon as the mean profitability of the industry creeps upwards due to its growth.

Miskatonic University

What is your creative process when working on a board game? Can you talk us through it?

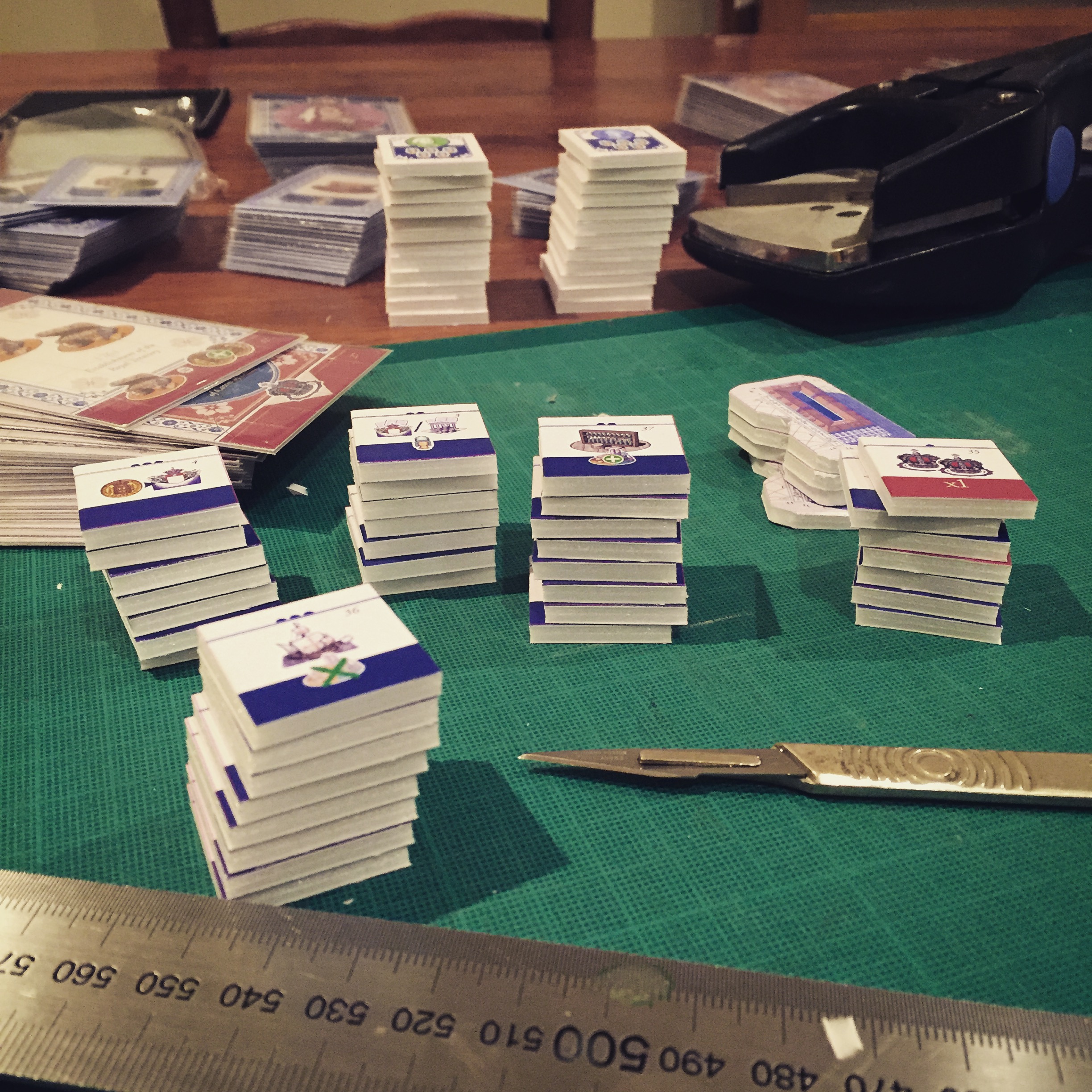

The first thing I always do is play the game. I’ll make a prototype, or sometimes the publisher will provide one, and I’ll get some people together and play it. During this I’m thinking about how the players interact with the pieces and the board. Is there a more elegant solution? Do we need all of those counters, or can we use a track instead? Is there a clearer way to present the information that will help players learn and play easier?

Then I start sketching ideas for each element, all rough thumbnails on paper. This is time for all of the big ideas. Do we need a board at all? Should the layout be portrait instead?

Depending on the game, there is sometimes a period of research involved at this point. For historical games I’ll look into the style of visual communication that was prevalent at the time, things like fabric patterns, building materials, costumes etc. Lisboa is a good example of this, as the artwork is very much rooted in the time period. Nemo’s War is another example of a game that needed a LOT of research, as I decided to find a reference for all 100+ ships depicted in the game.

After that I start to make a very rudimentary layout, using only boxes and circles to denote spaces etc. No “artwork” whatsoever. Depending on the complexity of the game I’ll usually make another prototype at this stage. The game should be fully playable, and this gives me a sense of the changes I’ve made to the ergonomics of the prototype.

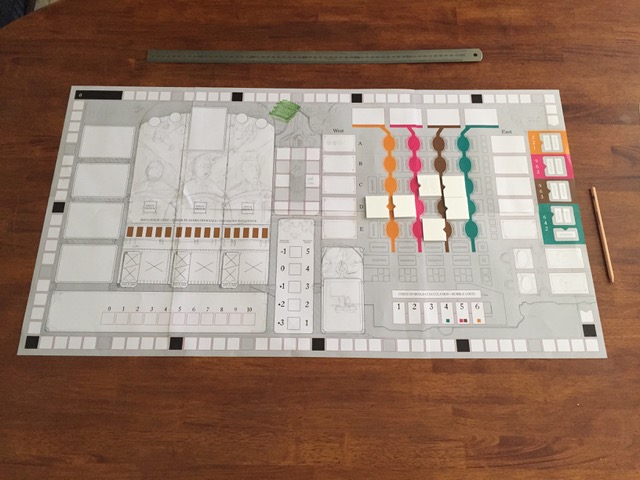

Lisboa in progress overview

If I’m happy with that, then it’s just a case of tackling the finished artwork in the most logical way. Sometimes that’s iconography first, or card layouts, or maybe the board. I tend to vary my style a lot for each game, so there’s always a stage of visual development and experimentation as well. I don’t tend to submit options on style or layout, preferring to commit and put my effort behind the solution I think will work best. The other reason for this is that the style often emerges during the first few hours of development, so creating a sketch in advance is often impossible, as I myself don’t know what it will end up looking like.

Once the game is almost finished, I’ll make another prototype and play it again, to catch little things that only become apparent when you ask people to play it.

Vinhos Deluxe

As regards tools, I use a pen and sketchbook a lot. Once I move to the computer I use the Adobe Creative Suite, primarily Photoshop, Illustrator and InDesign. I also do some 3D work in Cinema 4D. I typically build a 3D version of the game as I’m developing it, as I like to see how each element looks as part of the whole.

If you want to read more about the process of creating Lisboa, I’ve written a post on boardgamegeek detailing the development of the visual style, as well as the changes that were made to gameplay as a result of graphical solutions. You can find that here.

Nemo's War - Ship Counters

You mentioned finding references for all the ships in Nemo’s War, so in broad terms how much of a project do you spend on research, and how important is this phase in shaping what you create?

Reference is really important to me, if it’s available. For any game that even dips its toe in the real world I want to look at as much relevant reference as possible. Design styles of the time, common pattern forms, fashionable colours etc. Sometimes that reference becomes the heart of the visual identity of the project (Lisboa is the obvious example of this). Sometimes I will mix it with other anachronistic elements, such as in The Scarlet Pimpernel. It all depends on how important I feel that authenticity is to the game experience itself.

For Nemo’s War, it’s not enormously important that each ship is 100% accurate to its real-life counterpart, but what is important is that the seas are populated by ships that are unique, so that the narrative of the game comes to life that little bit more. Given that all of the ships did exist in real life though, it seemed obvious that seeking real reference was the thing to do.

You’ve been working on Stephenson’s Rocket recently so could you tell us a little bit more about it?

Stephenson’s Rocket was an interesting project for me, because the game already existed, fully formed. So it was easy enough for me to play it and assess the game very quickly. The very first thing that occurred to me was that the game felt old fashioned. This was mostly down to the fiddly nature of using paper money and stock cards, which kept the banker very busy. It became clear very quickly that the money was entirely unneeded, as players never spent it during the course of the game, it was simply points, so my first suggestion was to ditch it and move to a points track on the board.

Stephenson's Rocket overview

Another feature that bugged me was constantly having to visually check, or ask for, the number of shares in each company that a player was currently holding, so that was also removed for share tracks on the board, making all of that information easy to access and track.

The last, and somewhat more tricky part of the puzzle was the industry markers. In the original game, every city has three industry markers, each depicting one of a number of industries. The markers are small cardboards tokens, with the colour of the city and its name in very small writing. During setup, all of these need to be sorted and placed out on the board, it’s a big pain, and feels really clunky. After a bit of experimentation, I came up with a table system that lives on the main board, onto which players place their cubes instead of claiming markers. This has many benefits for gameplay. Firstly, it completely eliminates setup entirely. Secondly, the players can very easily see which cities provide which industry, and lastly, it allows the assessments of majorities in each of the industry types (for which points are awarded at the end of the game) very quick. The other benefit that this solution offers is that, as more maps are created for Stephenson’s Rocket, new industry markers are not required to maintain thematic accuracy (this is also true for currency).

The last element that was added was a player board, featuring an iconographic guide to the various scoring methods of the game, which can be a little tricky to remember at first. Other interesting elements to the project included creating a miniature for the famous locomotive, and coming up with a wooden design for the stations that could be placed on a hex at the same time as a locomotive. I also designed a pair of custom passenger meeples, replacing the tokens of the original game, which I think add a nice element of character to the overall presentation. We also added track joiner tiles as an aesthetic upgrade.

Stephenson's Rocket

All of these changes leads to Stephenson’s Rocket feeling a lot more modern without actually changing any rules (only the expression of them). Overall Stephenson’s Rocket was very enjoyable to work on, and Grail Games were very supportive of me taking a wrecking ball to a much-loved game.

This interview isn't the first time you've been featured on my site, gaining the top two places for my best Board Game Art of 2017 public vote. Without votes like these, how easy is it to gauge the feeling towards your work in the community? Also, how important is that feedback to you and are there any ways you seek it out yourself?

I’m fairly active on Twitter, so I usually get pretty immediate feedback when my work is released. Users on Boardgamegeek are also never shy about sharing their feelings! Good feedback is always really important. I’m pretty isolated over here in Australia, and only get to travel and meet most of my gaming contacts once a year at Spiel, so keeping in touch online is essential.

Nemo's War - box art

Hearing players get excited about the games I’m working on is also really gratifying, and of course, seeing them being played all around the world is really rewarding as well. I subscribe to all of my games on BGG, and do keep an eye on the threads. As long as feedback comes from a good place, and is respectful, I’m always happy to engage with players.

Certainly awards such as the ones you’ve created provide a nice opportunity for me to stop and reflect on the fact that players are enjoying my work, so that’s really great.

What are you currently reading, listening to or looking at to fuel your work?

I’m reading Authority, the second book of Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach trilogy, which I’ve only just started. I liked Annihilation a lot (and also loved the film). Before that I had just finished the Red Rising trilogy by Pierce Brown, which I enjoyed a lot. I’ve also just finished reading The Hobbit to my kids, which was a big deal for me.

Red Scare

What advice would you give to anyone wanting to work in the board game industry?

Get to know as many people as you can, don’t be afraid to ask questions. Try to help other people as much as possible and support what they’re doing. Engage with content creators, designers, other artists. Not just about work but about the games they’re playing and the things they create. That’s how opportunities are made. And speaking of opportunities, don’t wait for them to come knocking, you have to go out and make them happen.

Do you have any current projects underway, or coming up that you’d like (or are able) to tell us about?